This [modern] art is the work of your neighbors, your contemporaries, human beings who are crying out in despair for the loss of their humanity, their values, their lost absolutes, groping in the dark for answers. It is already late, if not too late, but if we want to help our generation we must hear their cry. We must listen to them as they cry out from their prison, the prison of a universe which is aimless, meaningless, absurd.

I wrote a while ago on the Effect on Art of the Loss of the Ideal. As the title suggests, modern art suffers from the loss of shared ideals, i.e., common spiritual goals that people believe to be true and worth aspiring to. This has made the creation and appreciation of art entirely subjective, leading to a complete breakdown in standards of beauty, authenticity, and value that hitherto helped distinguish good art from bad. The outcome has been a proliferation of obtuse, ugly, and meaningless forms that have been christened as “art”, and this in turn has debased the meaning of the word itself to include anything resulting from intentional human effort – cooking as art, accounting as art, negotiating as art, etc.

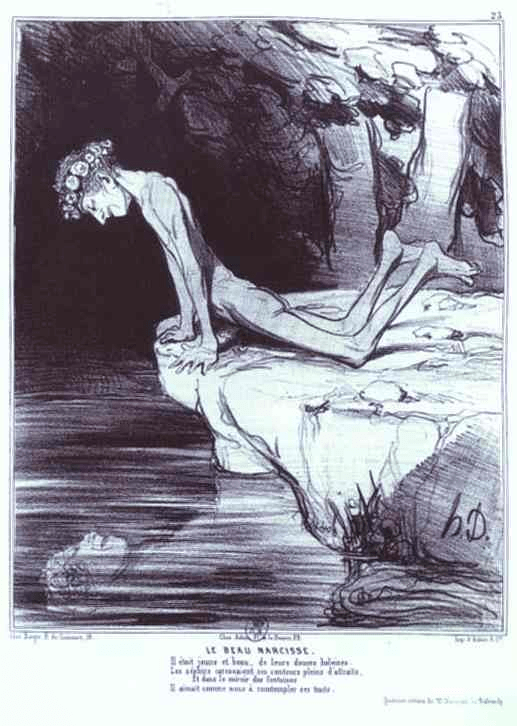

What I failed to capture in this earlier essay was that the meaningless of modern art is not just an outcome of nihilism and extreme subjectivity but also a cry of protest over the loss of just this spiritual ideal. Modern art is the mirror which shows modern man, bereft of God and higher values, in all his nakedness; look into your eyes: they are filled with terror; look at your gaping mouth: it is contorted in a silent scream. We are horrified and transfixed by this image of ourselves without the fine robe of transcendental morality and values, and as we clutch at where the folds of cloth once covered us, we grab nothing but empty air or our own unbearable flesh.

Modern art is ugly because man finds his unadorned nature ugly. Modern art is meaningless because man believes his existence is – in the absence of a higher truth, an ontology of existence, a transcendent creator-God – meaningless. Modern art is open to endless interpretation because man no longer believes in one single truth, only the claim to equal validity of every perspective. But in so being, modern art and culture do not represent merely an acceptance of this condition but more importantly, an anguished protest against it, a refusal to accept it as the final word on existence. To take the metaphor a bit further, modern art emerged when we looked at ourselves in the mirror and took the image to be reality – and when we believed we could not make ourselves beautiful, we either re-defined the meaning of beauty or sought to smash the mirror to pieces. The only real consequence was to show that rather than transcending our desire for beauty – for spiritual fulfillment, for meaning, for purpose – we are as beholden to it as ever, just morbidly incapable of attaining it.

The question, then, is: can we make ourselves beautiful? Were we ever beautiful, and if so, how did we lose our beauty? Was this a necessary outcome of mankind’s evolution, and does this really mean our desire for beauty – Nietzsche’s “metaphysical need” – is just an outmoded concept, a superstition of a more ignorant age, a biological redundancy that must be replaced by newer, more suitable values? Just what are these values?

These are the questions H. R. Rookmaaker grapples with from a Christian perspective in his seminal work Modern Art and the Death of A Culture. Rookmaaker wrote his doctoral thesis on the artist Paul Gauguin and went on to found the department of Art History at the Free University of Amsterdam. Although not apparent from the title, the work is an attempt by the author to found a Christian solution to the problem of modern art and culture. In so doing, he traces the evolution of the visual arts – i.e. painting – from the religious Middle Ages through the Renaissance and Enlightenment to the present-day (the late 1960s). Rookmaaker’s argument is that the present culture and its art are an outcome of the Age of Enlightenment, a time when human reason toppled religious belief as the primary source of human knowledge and experience. As a consequence, the delicate fabric of human belief and actions held together by faith in religious revelation was immediately unraveled, falling in a heap around man – revealing him as the “naked ape”.

Rookmaaker shows simply and with deep understanding how rationalism and empiricism forced man into a box by reducing his reality to only that which could be perceived by the senses and reasoned by the mind. This is how we lost our “beauty” – everything higher that made us human was now out of reach for man, the intellectual. Every ideal now was subject to the same scientific logic: can we see it? Can we hear it? Can we measure it? Can we weigh it? As these hammer blows fell, the next generation of thinkers arrived to question even these certainties. How can we know the next time we see it that it is the same thing? We can never know. And so, nothing really exists, there are no true facts or laws, just repetitions of experience that constitute a probability distribution of events.

Man in his eagerness to reach the precipice of knowledge found himself walking on a tightrope over the chasm of a complete loss of certainty – holding on precariously to the staff of self-knowledge as a biological machine subject to laws of causality that he dimly perceived and understood. He could no longer turn on his heels and return whence he came; if he didn’t progress, he would be blown into the maw of the abyss by a gust of wind. As he got further away from where he began, all he could see was the abyss, the rope, and the staff. Eventually, that was all that was real to him, and he knew himself only as the tightrope walker – man as machine, man as biological construct, man abandoned by God and certainty, cursed to live an unfree and precarious existence. The chasm stretches onwards to our own time, and the other end – if it exists, for it must, otherwise what anchors the rope? – is still not in sight.

Predictably, Rookmaaker offers a return to Christianity as the solution to our modern malady. In so doing he echoes Leo Tolstoy, who he curiously omits completely from his discussion of Christian attitudes to art. Tolstoy’s What is Art? is perhaps the most famous and cogent critique of modern art, accepted as universally valid despite being, like Rookmaaker’s work, a Christian perspective. Written in the late 19th-century, it finds no place in Rookmaaker’s otherwise wide and methodical survey of Christian attitudes to 19th-century post-Enlightenment art. Perhaps Tolstoy’s anarchical and radical interpretation of Christianity was too much for Rookmaaker, who is very much a by-the-Bible Christian, emphasizing repeatedly the need to accept on face-value the truth of the miracles, the life of Christ, and the writings of St. Paul – all of which Tolstoy treated with extreme skepticism and scrupulous criticism.

Rookmaaker doesn’t explain exactly how man is meant to return to a religious understanding of the world, especially when he rightly asserts that:

It is virtually impossible for man now to accept a religion he has invented. In this lie both modern man’s real tragedy, his despair, and his understanding of himself.

He shows a lot of respect for the talent and intellect of the 20th-century modern artists, including Picasso, but never ventures to explain why these superlatively intelligent men never considered the solution that was so readily available to them. Why would men capable of introspection, suffering, and artistic self-expression not turn to Christianity as the solution to the problem of their existence? If they didn’t, why should or how can we? Rookmaaker rails against bourgeois Christianity but doesn’t prescribe any concrete means for the modern man to accept Christ in his heart other than cultivating a deeper understanding of the Bible’s truth and the courage to act it out. Tolstoy was much more forceful and intentional in his solution: art must be reduced to a part-time activity, and the real contribution of the artist to society should be his labour. This was also the philosophy of the famous “peasant painter” Jean-François Millet, who along with the Barbizon school of painters is another notable absence from Rookmaaker’s brief survey of the few alternatives that existed in the wake of modern art.

That Christianity is the solution was neither surprising nor disappointing for me, since the book did a valuable job of summarizing art history and offering a cogent, engaging, and sincere critique of modern art from a respectful and analytical perspective. No one who reads it can deny it is true. What remains to be discovered is: how can we make ourselves beautiful? Our desire for it will never wane, no matter if the mirror is smashed or if the word is redefined. We have as yet no new vocabulary or experience of religion that does not hark back to those founded millennia ago. Obedience to these norms in a modern context through individual revelation – what Kierkegaard called the leap of faith – has worked for many, and that is just as well.

For others, perhaps, a silent spirituality, a quiet rejection of the corrupting influence of modernity, a lot of which we recognize in our heart but lack the courage to fight, will open our eyes, ears, and heart to universal truth and beauty through our individual and limited experience of them. As Rookmaaker says, to know Love exists one must first love someone. Instead of seeking an imaginary concept that we are not meant to find, we can honor the experiences of our daily life: the small kindnesses, the love for others, gratitude, and good happenings. Perhaps we should pick away slowly at the small things that bother our conscience, the little voice that makes itself heard whenever we know we are doing something wrong. This requires suffering, self-control, limitation of desire, and rejection of convenience. Little by little, perhaps we can come to a greater understanding of ourselves, becoming more thereby, and attain those ideals without even realizing it. In the words of a famous philosopher I quote often enough: he who reaches his ideal, thereby surpasses it.

Leave a comment